Value is the relative lightness or darkness of a shape in

relation to another. The value scale, bounded on one end by pure white

and on the other by black, and in between a series of progressively

darker shades of grey, gives an artist the tools to make these

transformations. The value scale below shows the standard variations in

tones. Values near the lighter end of the spectrum are termed

high-keyed, those on the darker end are low-keyed.

Value Scale

Value Scale

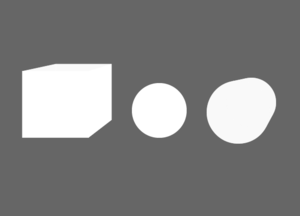

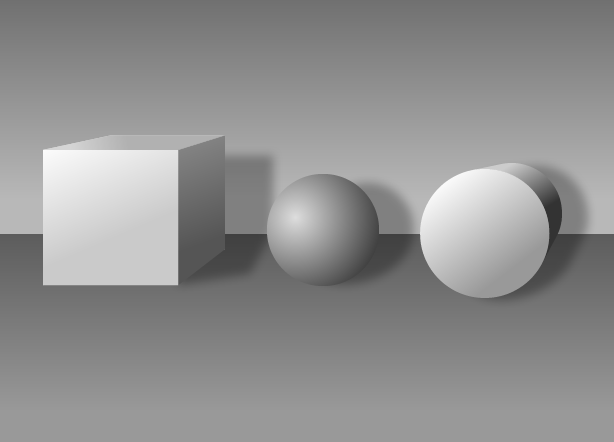

In two dimensions, the use of value gives a shape the illusion of

mass and lends an entire composition a sense of light and shadow. The

two examples below show the effect value has on changing a shape to a

form.

2D Form

|

3D Form

|

This same technique brings to life what begins as a simple line drawing of a young man’s head in Michelangelo’s

Head of a Youth and a Right Hand from 1508. Shading is created with line (refer to our discussion of

line earlier

in this module) or tones created with a pencil. Artists vary the tones

by the amount of resistance they use between the pencil and the paper

they’re drawing on. A drawing pencil’s leads vary in hardness, each one

giving a different tone than another. Washes of ink or color create

values determined by the amount of water the medium is dissolved into.

The use of

high contrast, placing lighter areas of value against much darker ones, creates a dramatic effect, while

low contrast gives

more subtle results. These differences in effect are evident in

‘Guiditta and Oloferne’ by the Italian painter Caravaggio, and Robert

Adams’ photograph

Untitled, Denver from

1970-74. Caravaggio uses a high contrast palette to an already dramatic

scene to increase the visual tension for the viewer, while Adams

deliberately makes use of low contrast to underscore the drabness of the

landscape surrounding the figure on the bicycle.

No comments:

Post a Comment